The storage layer of CockroachDB's architecture reads and writes data to disk.

If you haven't already, we recommend reading the Architecture Overview.

Overview

Each CockroachDB node contains at least one store, specified when the node starts, which is where the cockroach process reads and writes its data on disk.

This data is stored as key-value pairs on disk using the storage engine, which is treated primarily as a black-box API.

CockroachDB uses the Pebble storage engine. Pebble is inspired by RocksDB, but differs in that it:

- Is written in Go and implements a subset of RocksDB's large feature set.

- Contains optimizations that benefit CockroachDB.

Internally, each store contains two instances of the storage engine:

- One for storing temporary distributed SQL data

- One for all other data on the node

In addition, there is also a block cache shared amongst all of the stores in a node. These stores in turn have a collection of range replicas. More than one replica for a range will never be placed on the same store or even the same node.

Interactions with other layers

In relationship to other layers in CockroachDB, the storage layer:

- Serves successful reads and writes from the replication layer.

Components

Pebble

CockroachDB uses Pebble––an embedded key-value store inspired by RocksDB, and developed by Cockroach Labs––to read and write data to disk.

Pebble integrates well with CockroachDB for a number of reasons:

- It is a key-value store, which makes mapping to our key-value layer simple

- It provides atomic write batches and snapshots, which give us a subset of transactions

- It is developed by Cockroach Labs engineers

- It contains optimizations that are not in RocksDB, that are inspired by how CockroachDB uses the storage engine. For an example of such an optimization, see the blog post Faster Bulk-Data Loading in CockroachDB.

Efficient storage for the keys is guaranteed by the underlying Pebble engine by means of prefix compression.

For more information about Pebble, see the Pebble GitHub page or the blog post Introducing Pebble: A RocksDB Inspired Key-Value Store Written in Go.

Pebble uses a Log-structured Merge-tree (LSM) to manage data storage. For more information about how LSM-based storage engines like Pebble work, see log-structured merge-trees below.

Log-structured Merge-trees

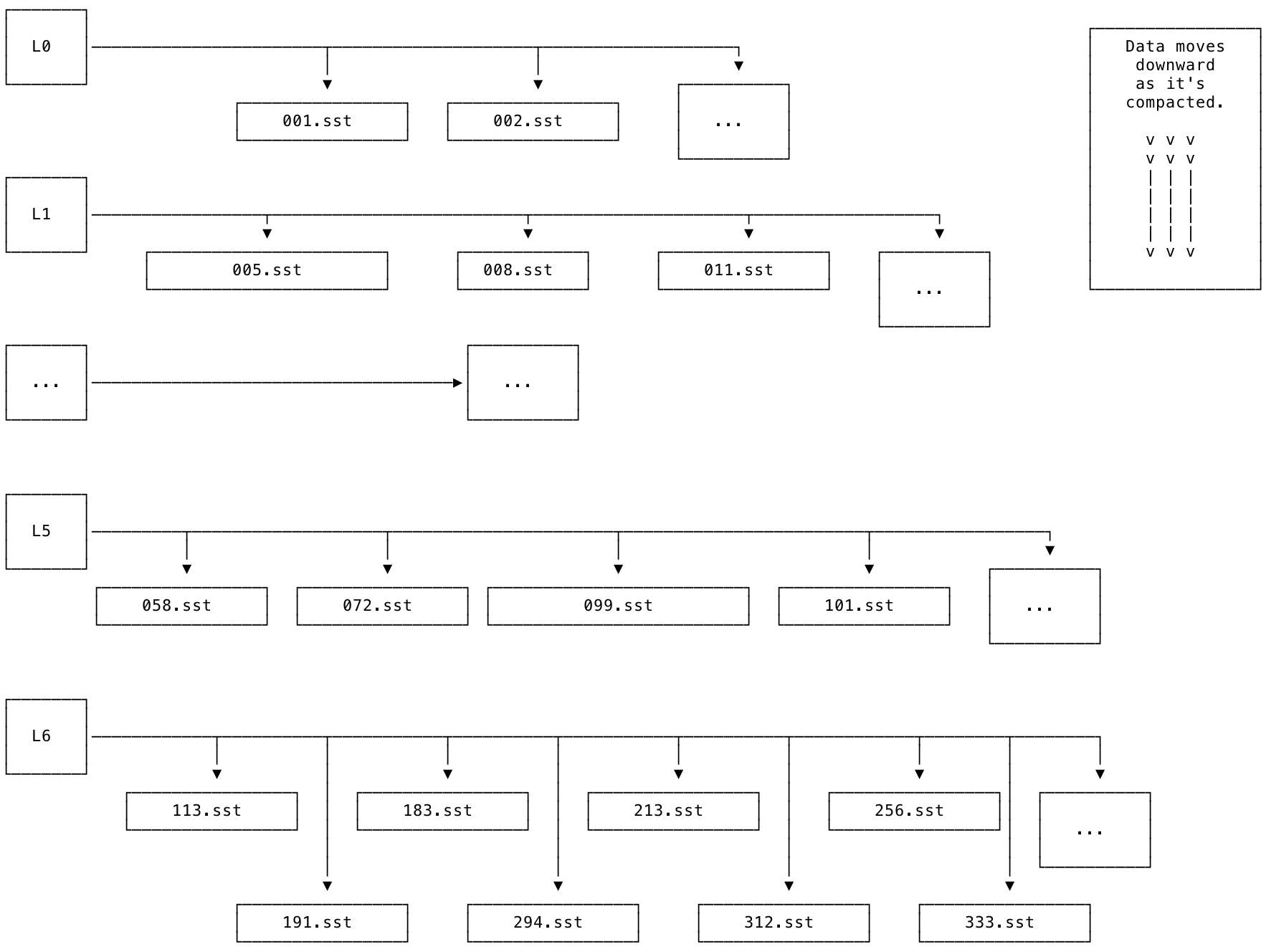

Pebble uses a Log-structured Merge-tree (hereafter LSM tree or LSM) to manage data storage. The LSM is a hierarchical tree. At each level of the tree, there are files on disk that store the data referenced at that level. The files are known as sorted string table files (hereafter SST or SST file).

SSTs

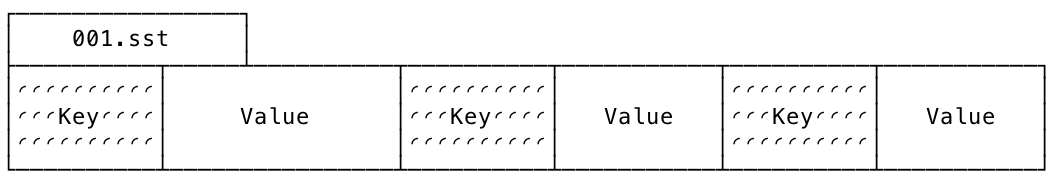

SSTs are an on-disk representation of sorted lists of key-value pairs. Conceptually, they look something like this (intentionally simplified) diagram:

SST files are immutable; they are never modified, even during the compaction process.

LSM levels

The levels of the LSM are organized from L0 to L6. L0 is the top-most level. L6 is the bottom-most level. New data is added into L0 (e.g., using INSERT or IMPORT) and then merged down into lower levels over time.

The diagram below shows what an LSM looks like at a high level. Each level is associated with a set of SSTs. Each SST is immutable and has a unique, monotonically increasing number.

The SSTs within each level are guaranteed to be non-overlapping: for example, if one SST contains the keys [A-F) (noninclusive), the next will contain keys [F-R), and so on. The L0 level is a special case: it is the only level of the tree that is allowed to contain SSTs with overlapping keys. This exception to the rule is necessary for the following reasons:

- To allow LSM-based storage engines like Pebble to support ingesting large amounts of data, such as when using the

IMPORTstatement. - To allow for easier and more efficient flushes of memtables.

Compaction

The process of merging SSTs and moving them from L0 down to L6 in the LSM is called compaction. The storage engine works to compact data as quickly as possible. As a result of this process, lower levels of the LSM should contain larger SSTs that contain less recently updated keys, while higher levels of the LSM should contain smaller SSTs that contain more recently updated keys.

The compaction process is necessary in order for an LSM to work efficiently; from L0 down to L6, each level of the tree should have about 1/10 as much data as the next level below. E.g., L1 should have about 1/10 as much data as L2, and so on. Ideally as much of the data as possible will be stored in larger SSTs referenced at lower levels of the LSM. If the compaction process falls behind, it can result in an inverted LSM.

SST files are never modified during the compaction process. Instead, new SSTs are written, and old SSTs are deleted. This design takes advantage of the fact that sequential disk access is much, much faster than random disk access.

The process of compaction works like this: if two SST files A and B need to be merged, their contents (key-value pairs) are read into memory. From there, the contents are sorted and merged together in memory, and a new file C is opened and written to disk with the new, larger sorted list of key-value pairs. This step is conceptually similar to a merge sort. Finally, the old files A and B are deleted.

Inverted LSMs

If the compaction process falls behind the amount of data being added, and there is more data stored at a higher level of the tree than the level below, the LSM shape can become inverted.

During normal operation, the LSM should look like this: ◣. An inverted LSM looks like this: ◤.

An inverted LSM will have degraded read performance.

Read amplification is high when the LSM is inverted. In the inverted LSM state, reads need to start in higher levels and "look down" through a lot of SSTs to read a key's correct (freshest) value. When the storage engine needs to read from multiple SST files in order to service a single logical read, this state is known as read amplification.

Read amplification can be especially bad if a large IMPORT is overloading the cluster (due to insufficient CPU and/or IOPS) and the storage engine has to consult many small SSTs in L0 to determine the most up-to-date value of the keys being read (e.g., using a SELECT).

A certain amount of read amplification is expected in a normally functioning CockroachDB cluster. For example, a read amplification factor less than 10 as shown in the Read Amplification graph on the Storage dashboard is considered healthy.

Write amplification is more complicated than read amplification, but can be defined broadly as: "how many physical files am I rewriting during compactions?" For example, if the storage engine is doing a lot of compactions in L5, it will be rewriting SST files in L5 over and over again. This is a tradeoff, since if the engine doesn't perform compactions often enough, the size of L0 will get too large, and an inverted LSM will result, which also has ill effects.

Read amplification and write amplification are key metrics for LSM performance. Neither is inherently "good" or "bad", but they must not occur in excess, and for optimum performance they must be kept in balance. That balance involves tradeoffs.

Inverted LSMs also have excessive compaction debt. In this state, the storage engine has a large backlog of compactions to do to return the inverted LSM to a normal, non-inverted state.

For instructions showing how to monitor your cluster's LSM health, see LSM Health. To monitor your cluster's LSM L0 health, see LSM L0 Health.

Memtable and write-ahead log

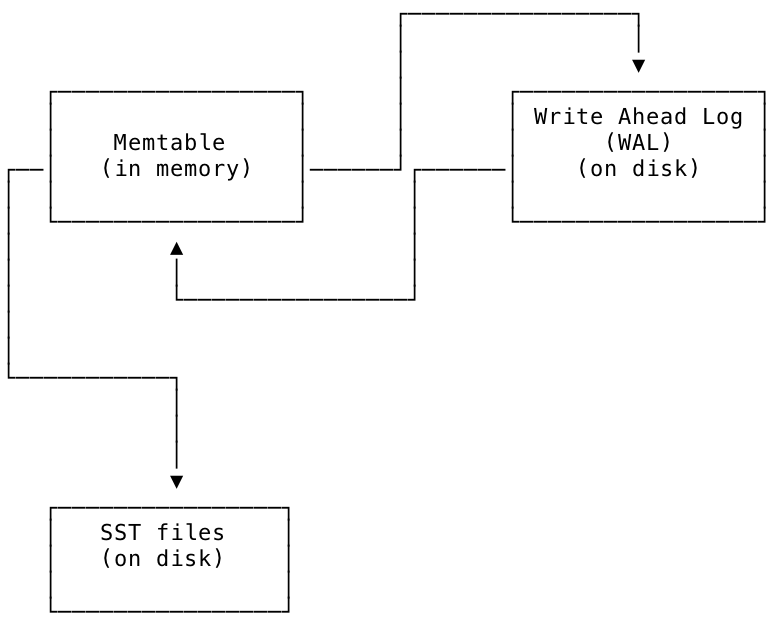

To facilitate managing the LSM tree structure, the storage engine maintains an in-memory representation of the LSM known as the memtable; periodically, data from the memtable is flushed to SST files on disk.

Another file on disk called the write-ahead log (hereafter WAL) is associated with each memtable to ensure durability in case of power loss or other failures. The WAL is where the freshest updates issued to the storage engine by the replication layer are stored on disk. Each WAL has a 1 to 1 correspondence with a memtable; they are kept in sync, and updates from the WAL and memtable are written to SSTs periodically as part of the storage engine's normal operation.

The relationship between the memtable, the WAL, and the SST files is shown in the diagram below. New values are written to the WAL at the same time as they are written to the memtable. From the memtable they are eventually written to SST files on disk for longer-term storage.

LSM design tradeoffs

The LSM tree design optimizes write performance over read performance. By keeping sorted key-value data in SSTs, it avoids random disk seeks when writing. It tries to mitigate the cost of reads (random seeks) by doing reads from as low in the LSM tree as possible, from fewer, larger files. This is why the storage engine performs compactions. The storage engine also uses a block cache to speed up reads even further whenever possible.

The tradeoffs in the LSM design are meant to take advantage of the way modern disks work, since even though they provide faster reads of random locations on disk due to caches, they still perform relatively poorly on writes to random locations.

MVCC

CockroachDB relies heavily on multi-version concurrency control (MVCC) to process concurrent requests and guarantee consistency. Much of this work is done by using hybrid logical clock (HLC) timestamps to differentiate between versions of data, track commit timestamps, and identify a value's garbage collection expiration. All of this MVCC data is then stored in Pebble.

Despite being implemented in the storage layer, MVCC values are widely used to enforce consistency in the transaction layer. For example, CockroachDB maintains a timestamp cache, which stores the timestamp of the last time that the key was read. If a write operation occurs at a lower timestamp than the largest value in the read timestamp cache, it signifies there’s a potential anomaly and the transaction must be restarted at a later timestamp.

Time-travel

As described in the SQL:2011 standard, CockroachDB supports time travel queries (enabled by MVCC).

To do this, all of the schema information also has an MVCC-like model behind it. This lets you perform SELECT...AS OF SYSTEM TIME, and CockroachDB uses the schema information as of that time to formulate the queries.

Using these tools, you can get consistent data from your database as far back as your garbage collection period.

Garbage collection

CockroachDB regularly garbage collects MVCC values to reduce the size of data stored on disk. To do this, we compact old MVCC values when there is a newer MVCC value with a timestamp that's older than the garbage collection period. The garbage collection period can be set at the cluster, database, or table level by configuring the gc.ttlseconds replication zone variable. For more information about replication zones, see Configure Replication Zones.

Protected timestamps

Garbage collection can only run on MVCC values which are not covered by a protected timestamp. The protected timestamp subsystem exists to ensure the safety of operations that rely on historical data, such as:

Protected timestamps ensure the safety of historical data while also enabling shorter GC TTLs. A shorter GC TTL means that fewer previous MVCC values are kept around. This can help lower query execution costs for workloads which update rows frequently throughout the day, since the SQL layer has to scan over previous MVCC values to find the current value of a row.

How protected timestamps work

Protected timestamps work by creating protection records, which are stored in an internal system table. When a long-running job such as a backup wants to protect data at a certain timestamp from being garbage collected, it creates a protection record associated with that data and timestamp.

Upon successful creation of a protection record, the MVCC values for the specified data at timestamps less than or equal to the protected timestamp will not be garbage collected. When the job that created the protection record finishes its work, it removes the record, allowing the garbage collector to run on the formerly protected values.

Interactions with other layers

Storage and replication layers

The storage layer commits writes from the Raft log to disk, as well as returns requested data (i.e., reads) to the replication layer.

What's next?

Now that you've learned about our architecture, start up a CockroachDB Serverless cluster or local cluster and start building an app with CockroachDB.